By Bran Poster, Photos by Jermaine Hudson

Tobacco, textiles and… tables? Until recently, I never thought of furniture as a pivotal part of our state’s heritage. Honestly, I seldom thought of furniture at all: it was just another aspect of life to be taken for granted like clean tap water or air conditioning. It took but one visit to the NC Museum of History’s “Furniture: Crafting a North Carolina Legacy” exhibit to reassemble my conception of furniture and the role our state plays in it. I will try to get you excited about going by sharing some of the context behind it, without too many spoilers of what you’ll witness within.

The exhibit is the brainchild of the museum’s decorative arts curator, Michael Ausbon, who sought to call attention to this part of our state’s story in light of increasing globalization and a revival in custom furnishings.

“The furniture industry has really suffered in the past few years, with the industry going overseas and a lot of cheap imports into North Carolina,” said Ausbon. “I wanted to bring back to everybody’s attention all the history that the furniture industry has brought to the state.”

Ausbon split the exhibit into ten sections, beginning with the small-scale cottage artisanship that went on before the Industrial Revolution. Until the mid-to-late 1800s most furniture manufacturing in North Carolina was done by farmers rather than dedicated craftspeople. They would farm in the spring and summer, and then produce furniture in the fall and winter months. This all changed with the advent of new technologies and entrepreneurs like Thomas Day, a free African American cabinetmaker. A statue of Day is seen on the front steps of the museum.

“We call him the father of North Carolina’s furniture industry, because around the 1840s-1850s, he was making 11.9% of all the state’s furniture, which was unbelievable,” said Ausbon. “He really owned what I would say was the first factory in North Carolina.”

People with strong business acumen weren’t the only thing helping industrialize our furniture production, however. Factors like new railroads and an abundance of timber made our state an ideal place for a dedicated furnishing industry to flourish.

“It was this perfect coming together of the lumber, the cheap labor, the railroads, and then also the community supported it,” Ausbon said. “Communities got together and said, ‘Hey, we want the furniture industry here.’”

The industrialization of furniture wasn’t popular with everyone, though. The shoddy quality of both the working conditions and the furnishings produced in many early factories led to a backlash called the Arts & Crafts movement.

“It was a group of artisans and concerned citizens at this same time coming together,” Ausbon said. “There was this consciousness in certain groups of artisans, and also in religion of making sure that crafts and people are treated appropriately.”

The Arts & Crafts movement was but one of the many byproducts of North Carolina’s growing furniture industry. Mirror-makers, shipping and crating companies, magazines and photography studios all emerged to support the burgeoning business.

One such furniture-adjacent contraption that features prominently in the exhibit is the Lineberry cart, which was used to move lumber and finished goods across factory floors and onto train cars. Its manufacturers advertised that you could put a ton of lumber on it without it creaking or groaning: I invite you to judge this for yourself!

The subsequent section about early women leaders in the furniture industry has a downright inspiring cast of characters. Myrtle Hayworth Barthmaier, who became president of four different furnishing-related companies after her husband died in 1928, comes to mind immediately.

“She was actually the only woman to run a factory through the Great Depression, and through World War I and II,” Ausbon said. “And she also did that while she was raising six kids.”

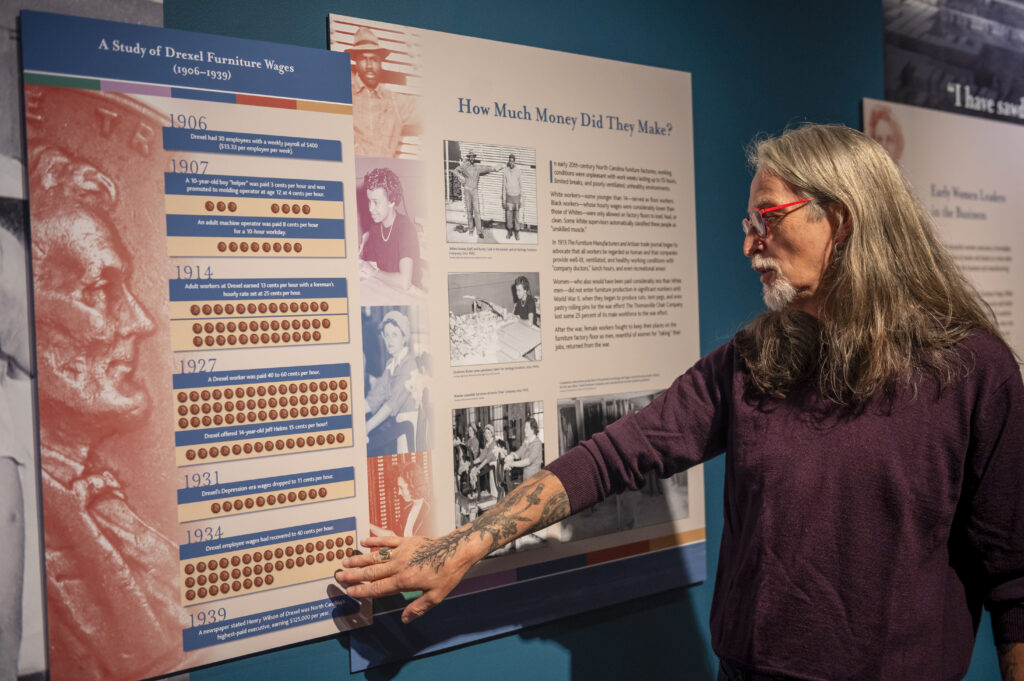

Speaking of kids, if you were a 10-year-old back in 1907, you could’ve gotten yourself a job at your local furniture factory! You’d be paid a whopping 3 cents an hour, which would translate to a little over a dollar after inflation. This is from the exhibit’s infographic on furniture employee earnings, which I found to have some disturbing parallels to wage disparities today.

The beginning of the 1930s and ‘40s saw a crucial transformation for the furniture industry. Soldiers returning from both world wars had observed ancient European cities and traditions going back thousands of years, and longed to have American furnishings reflect a similarly venerable precedent.

“There was this sense for America of recapturing the history that people had forgotten about, or hadn’t really appreciated,” Ausbon said. “The furniture companies saw that as well, and what they started doing was going back and copying antique furniture from our past.”

By the ‘50s and ‘60s, however, consumers started getting sick of the old stuff. In response, many manufacturers turned to architecture for inspiration. A North Carolina company called Broyhill designed an entire collection of furniture based on modernist buildings in Brasília, the capital of Brazil. Frank Lloyd Wright, while known primarily for his buildings, developed furniture pieces as well. It’s fascinating to contrast the works of these designers seen in the exhibit with the architectural styles that inspired them.

Despite its beauty and sophistication, the monumental furniture production going on in our state was bound to have a calamitous environmental impact, and Ausbon wastes no time in exposing it. In just 22 years after 1900, the furniture industry annihilated 300,000 acres of virgin timberland, an area more than half the size of Wake County.

Today, it’s estimated that Americans discard 12 million tons of furniture every year. Good has come from the bad, however: artisans have found an inventive way to mitigate this tremendous waste by “upcycling,” or creatively repurposing, older used furniture. The final section of the exhibit displays some particularly gorgeous examples of this phenomenon, from a bench repainted by folk artist Sam “The Dot Man” McMillan to an antique recreated by Cornelio Campos, the first Hispanic artist to win a North Carolina Heritage Award.

Ausbon stressed the interconnectedness of the environment, furniture and people, which too often goes unnoticed.

“All this furniture has touched so many lives, from designers, to makers, to owners,” Ausbon said. “It’s so cyclical.”

The exhibit will remain open through March 2024. Admission to the North Carolina Museum of History is completely free. In addition, the museum offers a number of educational programs and events. For more information, visit their website at ncmuseumofhistory.org